Last friday december 4th 2020 Catriona Casali came to my houseboat to do an interview with me. The interview is part of her eduction. I think it turned out really well. You can read it in this blog.

Interview with Obed Brinkman

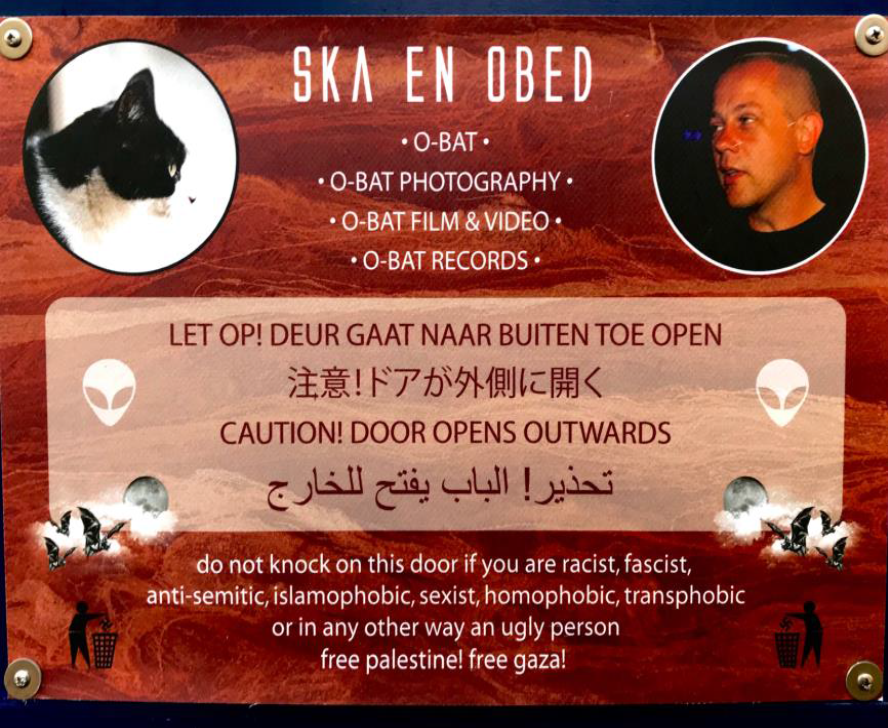

On June 22nd 2019, at the height of the Black Lives Matter protests, I attended a demonstration in Emmen. As I stood there scanning the shade-less asphalt square, my eyes rested on a man dressed who was quickly moving cameras and microphones between activists and journalists near the stage. He was small, dressed in black, and carried an air of quiet expertise. His name was Obed Brinkman, and he was my mailman. Six months later, I find myself arriving at Obed’s houseboat, with a backpack full of notebooks and beer. On the door there is a sign that says CAUTION! DOOR OPENS OUTWARDS in Dutch, Japanese, English, and Arabic. In a reversal of roles I knock on his door, and Obed opens it with a shy smile.

In your activism, you are a musician, photographer, filmmaker, and blogger, and community organizer. Am I missing anything?

No, I think that covers it.

Of all of these skills, which was your first love?

Music. When I was younger, all I wanted to do was play trombone.

Do you think that music has influenced your activism?

Well, I tried to combine the two, later. I used to just write instrumental songs, but then I slowly started writing lyrics about injustice, and then really clear rhythms, like “we don’t want you Nazi scum” or songs against Monsanto, and stuff like that.

[laughs] I have seen the music videos. I am interested in your demonstration organizing, and the mobilization work that you do. I am curious about how this started; can you tell me about the first demo that you attended?

I was just a kid, my mother took me to a demonstration against nuclear power being used in the Netherlands, and the rise of nuclear energy.

Do you know how old you were?

Possibly nine or ten.

Do you remember what it felt like to be there, what the energy was like?

I don’t have a lot of memories about it, but I remember it was a vibrant energy.

How about your first demonstration as an adult?

I don’t remember exactly which one was my first, but we did some demos in Groningen against budget cuts in the school system… we got into an official building and squatted it, and then the police came and we told them we were going to stay until the law changed [laughs].

How long did the occupation last?

Ah, I think one day or so.

How did you feel during this occupation?

It was exciting because it was illegal to just break into a building. It was organized by some people who had experience with this type of action.

So many of us, including myself, have strong feelings and positions about the injustices of the world but we don’t do anything about them. You do things. I am wondering, what was the transition there for you?

There is so much injustice in the world. My activism doesn’t change a whole lot of things, but still, every step counts and I’d rather be active than do nothing. If I do nothing there’s one more point for injustice, but if I do something, then at least my voice has been heard.

It’s a drop in the bucket, but it’s better than no drop in the bucket.

Exactly. The other day, some people in Groningen organized against new legislation in Poland, which would criminalize abortion. Worldwide there were a lot of demonstrations about this issue. There were so many protests about this topic worldwide that the Polish government decided to wait before passing the law. So, these things happen, and when you read about people saying ‘oh, you can protest but it doesn’t do anything’… well, it does sometimes.

You saw this also with the Black Lives Matter protests. There were so many policy changes that occurred after those that wouldn’t have occurred otherwise.

Absolutely. The BLM protest era last year, and of course it’s still going on, but at the peak it was a really inspiring time. You felt in the air that something was changing.

So we’ve discussed demos that you have attended; which was the first one that you organized by yourself?

The first one I did by myself was the free Gaza demonstration at the Groningen train station.

When was this?

I think three years ago.

And how did it go, what was the turnout?

It was good; there were three music acts and five speeches

Wow, that’s a huge success for your first demo!

[laughs] Yeah. Some people turned up, and there was not a lot of media coverage, so I had to call journalists and ask ‘can you please write something about this?’, because people don’t want to look at what is happening in Gaza and Palestine.

They may not want to look at the issues, but it’s newsworthy when you have three musical acts at the train station. Do you think they’re really avoiding covering the event because they don’t want to publish anything about Gaza or Palestine?

Well, it’s a sensitive topic in the Netherlands, and I think not only in the Netherlands. A lot of people see it as a complex issue, which in a way it is, but in a way, it isn’t. The people in the Gaza area suffer a lot, and I think this has to change.

Of course. How did it feel to be at this event that you’d organized?

I was glad that it succeeded [laughs], because it was all organized by me, and if something had gone wrong I would have been responsible. So, I was quite anxious.

How many demos have you organized at this point?

By myself I think four, and with others another four or so.

Which of these was the most memorable demo for you, and why?

[long pause] I think two… there was one anti-racism demo that I organized in the Grote Markt, and Jerry Afriyie [Dutch activist and leader of anti-racist group, Kick Out Zwarte Piet] came all the way from Amsterdam to speak, and his speech was really inspiring. The other one was with a group of anti-fascists that I’d joined, and we went to this restaurant where some far-right representatives were having a meeting, and the police also showed up and I remember the feeling of intense tension in the air. It all went well, but it could have gone very wrong.

Tell me about the Black Lives Matter demonstration that you organized in Emmen.

It was actually a coincidence, some people were organizing a Black Lives Matter demonstration in Emmen, and then a friend of mine called and asked if I would help to organize there as well,

so there ended up being two groups of organizers and we fused them together into one demonstration.

Did the demonstration in Emmen feel different from your typical demonstration in Groningen?

Yeah, because there was a lot of resistance in Emmen against this demo. On the internet I was getting messages, some guy wrote to me asking if I was sure I wanted to come to Emmen because I wasn’t wanted there, and a lot of people were worried about violence breaking out. I think there were about 25 extreme-right people at the demo, but they couldn’t do anything.

I remember this. They were standing right behind me and I was filming forward, and would them quickly sweep around with my camera, to catch their faces just in case violence broke out and we needed the footage for identification. [laughs] I remember thinking, ‘please don’t beat me up’.

[laughs] Yeah, yeah.

And there were so many cops across the street on the other side.

Yes it was crawling with cops, so the counter-demonstrators couldn’t do anything. I’m not a real fan of the police, but in this case it’s good that they were there.

I had mixed feelings about the police presence as well. I remember at the end of that demo there was an announcement asking us to get rid of our signs before leaving the area. Why was that?

Because people were afraid that once the demo was over and everyone started spreading into the city, that there was a risk of the demonstrators getting beaten up or arrested.

Is this common?

Yes, it has happened before. Extreme right demonstrations and counter-demonstrations don’t pose much danger during an event, but at the point when people start heading home, this is when it can be dangerous.

Do you expect the potential for violence to grow in the future, that demonstrators will have to keep an awareness of covering slogans and throwing away signs on their way home?

I don’t know, we’ll see how it goes. I think the tension within the extreme right and alt right movements is still on the rise.

After that demo in Emmen, you had some trouble with your job.

It was actually leading up to the demo. A few days before, somebody called my job and said ‘Your mailman is threatening people and shouting at people who don’t agree with his views on Black Lives Matter’. I got a phone call from somebody high up in the postal company I work for, and he met me on the street and explained what the complaints were, and I had to deny it like three times, and then I think he believed me. It all went well in the end, but if he hadn’t believed me I think I would have lost my job.

So, going back to this phone call. You do bicycle deliveries, so you’re either walking or cycling, and then your phone rings and it’s your boss. What does he say?

He just said, ‘I want to talk to you, where are you now?’ and I told him where I was, and he said ‘ok, stay there’.

What went through your mind at this time?

I thought ‘this must be really important’, because this never happens, they almost never call me. When they show up in person, that means it’s really important [laughs].

Yes, because you’re so mobile at your job it must be hard for them, they have to come and find you on whichever side street you happen to be on, and hold up the whole mail route.

Yeah.

How long have you been working as a post-perosn?

For eight years. This is a good thing, because if I was really someone who would yell at people on the street there would have already been a lot of complaints.

If they had fired you, what would you have done?

I would have tried to fight their decision, because the accusation was just not true. I would have gone to the media to make a story out of it. After that I wouldn’t know what to do, because my only formal education is in music. Maybe clean houses.

Since this incident, have you publicly organized any other demos?

Yes, I organized Free Gaza/Free Palestine, the second edition, on the Grote Markt.

Were you not afraid that someone else would make a phone call to your job?

[laughs] Yes, it could have happened. But I keep going. I was also involved in a squat incident; somebody asked me to stay over in a newly squatted house because there weren’t so many people staying there, and there was a lot of resistance from the neighbors and some threats from hooligans. I said I’d join them, and I stayed the night. At seven the next morning the police came and broke down the door and arrested all of us, so I was in jail for the whole day. My job tried to call me that day and I didn’t have my phone on me of course, so the next day I called them and was honest about what had happened, and again they believed my story [laughs]. So I got lucky again. We got released at nine in the evening.

Were you meant to work that day?

No, it was a coincidence because I had cut my thumb on a mail slot and it had gotten infected, so I had three days off of work to let it heal. It was my luck.

You told me on the phone that you’ve experienced harassment in response to the demos you organize and the music that you make. You cover many topics in your activism; do certain topics bring on more threats than others?

Yes, the PVV period [in 2015] brought a lot of threats, negativity, and name-calling.

What names did they call you?

They responded to the music that I made, saying things like ‘you all smell bad’ and ‘you look like shit’, ‘none of you have a job’, you’re all alcoholics’, ‘you’re getting money from the state to make this’, and so on.

And what kinds of threats did you get?

That I have to look out when I walk on the street, that they are after me. That they will beat me up and sink my houseboat. My address was on the internet.

Your address? Did you ever feel that you were really in danger?

In the beginning I was really overwhelmed by all of it, and at a certain point it got so intense and there were so many messages that I found an address where I could hide for some time. I wasn’t really scared for myself, I was scared that they were going to sink my boat or do something to my cat. Those were my real concerns. But right before I left, the storm quieted. There was a famous Dutch TV host who said that Dutch people should reconsider the Zwarte Piet element of Sinterklass, and everyone left me alone and went for him instead.

They found a bigger fish to chase.

Yeah, absolutely.

When these people are messaging you, do you ever engage with them?

No. I did once reference the comments in an interview with a local television network, and I said that people message me and only talk about the way that my friends and I look, and never engage with the points that I am trying to make in the video. It is never about the things I say in the song, only about appearances, and making stupid threats. After I said this in the interview, one guy messaged me and said ‘I saw your interview and I’m sorry about what I did’, so that was really nice.

That must have been gratifying.

It was, I think I opened his eyes a little bit. He seemed like a young guy sitting behind his computer and typing a lot of nonsense, not really understanding the impact of his behavior.

So these people that are taking the time to find your contact information, mock you, and threaten you, they clearly have strong feelings about these topics. You also have strong feelings about these topics. If you had the opportunity to sit down and have a civil conversation with them, what would you say?

The biggest problem with them is that they’re typing anonymously, and that’s really cowardly. Why not just talk to me? Talk to me about my ideas, and tell me about yours. It would at least be a much more honest way of communicating.

You have a gift for mobilizing people around a cause, which is so important in activism. It also makes you a pretty obvious target. Have you considered changing the way that you do activism, to be more behind-the-scenes?

No. In 2015 when I made the Fuck de PVV music video and my face and address were all over the internet, I made the decision not to try and be anonymous because there’s no use, I’m already out there. I don’t feel that I should hide my fight against injustice… for me, that wouldn’t feel good. How can you not take a stand against injustice?

That being said, I am really happy that there are a lot of new activists on the rise in Groningen, because sometimes organizing takes a lot of my energy. It’s nice to just go and help out with the stage or do some sound engineering, or take some pictures.

That brings me to my final question. There are so many fresh faces to activism in Groningen, such as the Groningen Feminist Network and Black Ladies of Groningen, most of whom are students and are relatively young. You’ve been doing this for a long time. What would you say to them that you wish someone would have said to you when you first started out with community organizing?

[long pause] I think they’re doing a really good job, to be honest. I’m really impressed by some of their recent actions. There was a recent demonstration against the conditions in Camp Moria, and the demo against the Polish legislation banning abortion. These actions were organized so well that I wouldn’t know what to say to them.

Thank you so much for this interview.

No problem.

© Catriona Casali 2020